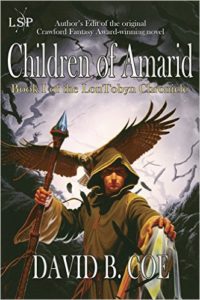

Recently, I released the Author’s Edit of my first published novel. Children of Amarid, and its sequels, The Outlanders and Eagle-Sage, which I have also revised for re-issue later this year, made up my first trilogy, the LonTobyn Chronicle. Originally released in the late 1990s, these books established me critically and commercially, and won me the Crawford Fantasy Award as best new author.

Despite their flaws (most of which I’ve addressed in these Author’s Edits), I love these books, both for how they turned out, and for what they represent in the context of my career. Children of Amarid percolated in my mind for years before I finally committed the story to paper, and its publication seemed at the time like the culmination of my lifelong dream of becoming a professional writer. I say “seemed at the time” because I now realize that the dream itself is ongoing. Those of us fortunate enough to write for a living dream all the time of the next project, the next career milestone. I’m no different. But when it was released I thought of the book as the end of a long struggle, rather than as the jumping off point for a new adventure.

Despite their flaws (most of which I’ve addressed in these Author’s Edits), I love these books, both for how they turned out, and for what they represent in the context of my career. Children of Amarid percolated in my mind for years before I finally committed the story to paper, and its publication seemed at the time like the culmination of my lifelong dream of becoming a professional writer. I say “seemed at the time” because I now realize that the dream itself is ongoing. Those of us fortunate enough to write for a living dream all the time of the next project, the next career milestone. I’m no different. But when it was released I thought of the book as the end of a long struggle, rather than as the jumping off point for a new adventure.

I came to fiction writing from a career in academia, and when I entered publishing, the world was a different place: Amazon.com was a struggling start-up that sold only books, and people were actually impressed that as a newly-published author I had my own website! <Gasp!> Many of my experiences from those early years don’t translate to the publishing industry as it exists today. Others remain as relevant now as they ever were. So I thought I would share a few early lessons from the “firsts” I experienced when the LonTobyn books hit the shelves.

Probably the most difficult “first” of the process was the revision letter for Children of Amarid I received from my editor. I knew that I would need to revise the book before it could be published. Kind of the way I knew I would need to rotate the tires on my car at some point. I acknowledged it as part of the production of the novel, but I gave no thought to what it actually meant. Talk about rude awakenings.

Don’t get me wrong. I understood that my first novel wasn’t perfect. I was sure I’d misplaced a comma or two and used a wrong word somewhere in chapter sixteen. But I was blind-sided by that first letter from my editor. Turns out my new baby had warts. Lots of them. Big, nasty ones. Looking back on the novel for the purposes of re-issuing the books this year, I realize that with all he pointed out to me, he ignored some stuff. I think it was the editorial equivalent of triage. Do what we can to save the patient and deal with the lesser stuff another time. I had prose problems, character issues, inconsistencies in my world building, plot holes that the space shuttle could have flown through.

Clearly the book was good. Editors don’t buy books out of charity. But it had problems, and I didn’t see them. I was too close to it, too inexperienced. My first reaction was the worst one possible. I got mad, and I went so far as to pick up the phone to tell him how wrong he was about this and that. Putting down the phone without punching in his number was, with the singular exception of asking my wife to marry me, the smartest thing I’ve ever done. Instead of making the call, I read his letter again. And again. I read through his margin comments. I argued with him the entire time, but he never heard a word of it. With time, I came around to seeing his point on nearly every issue. I fought him on a few things, but I realized that his twenty plus years in the industry were worth something, and that he wasn’t my opponent in a clash of wills and egos. Rather he was an ally who wanted the same thing I did: the best possible book.

So that’s lesson number one: Listen to your editor and/or beta readers. They’re trying to help. They want what you want. Acknowledging the flaws in our work doesn’t weaken us or our books. It’s the first step toward making them as good as they can be.

I remember waiting to hear from my agent (a family friend who worked in publishing and agreed to serve in that capacity) about whether my first book had sold. I imagined what it would be like to have that first contract in hand. I had an idea of what my first advance would be. It was a ridiculous idea, entirely without foundation and divorced from reality, but it certainly was an idea. When the offer came in, my agent was so pleased. I was stunned speechless. How did any writer eke out a living making so little money? My wife had a great job with benefits, and she offered to support us while my career got off the ground. But dear Lord, that first advance was a pittance. Take out the agent fees, break the advance into pieces (half on signing and half on delivery, and we were lucky to get such good terms) and it was a fraction of a pittance.

Lesson number two learned: Writing is not a path to wealth and fame. Most writers make very little, too little to get by without a supportive, gainfully employed spouse and/or a day job. Fortunately, we were doing fine. But here’s the point. I was writing then, and I continue to write now, because I love the craft, I love the life, I love the challenge. If you don’t love it, don’t do it. Because as jobs go, it’s low-paying, highly uncertain, ego-battering, lonely work.

The third “first”: The first time I saw a novel of mine in print. As it happened, the local bookstore received their shipment of books before I received my author copies from the publisher. The store manager called me, and my wife and I drove over to see them. She had to drive. I was too excited. Holding that book in my hands, seeing the jacket art, the map, my words in typeset print — the thrill defies words. I have two children, and it wasn’t quite as amazing as holding them for the first time. But it was pretty cool. And it remains a thrill to this day. Each time I receive my copies of a new book, I take a moment to celebrate the achievement, to savor the physical realization of a creative vision.

And in many ways this is the most important lesson: Don’t take it for granted. Whatever level of achievement we have reached in our writing, there is always something further for which to strive. It’s too easy to sublimate our appreciation for what we’ve attained beneath our ambitions for successes as yet unrealized. Resist that tendency. I would never suggest that we abandon the dreams and goals. Ambition is good. But we should also take the time to recognize our accomplishments thus far. This is hard, and every milestone deserves to be feted.

*****

CHILDREN of AMARID is now available at your favorite online bookseller!

David B. Coe/D.B. Jackson is the award-winning author of nineteen fantasy novels. As David B. Coe, he writes The Case Files of Justis Fearsson, a contemporary urban fantasy from Baen Books. The first two books, Spell Blind and His Father’s Eyes came out in 2015. The third volume, Shadow’s Blade, has recently been released. Under the name D.B. Jackson, he writes the Thieftaker Chronicles, a historical urban fantasy from Tor Books that includes Thieftaker, Thieves’ Quarry, A Plunder of Souls, and Dead Man’s Reach.

David is also the author of the Crawford Award-winning LonTobyn Chronicle, which he is in the process of reissuing, as well was the critically acclaimed Winds of the Forelands quintet and Blood of the Southlands trilogy. He wrote the novelization of Ridley Scott’s movie, Robin Hood. David’s books have been translated into a dozen languages.

He lives on the Cumberland Plateau with his wife and two daughters. They’re all smarter and prettier than he is, but they keep him around because he makes a mean vegetarian fajita. When he’s not writing he likes to hike, play guitar, and stalk the perfect image with his camera.

http://www.DavidBCoe.com

http://www.davidbcoe.com/blog/

http://www.dbjackson-author.com

http://www.facebook.com/david.b.coe

http://twitter.com/DavidBCoe

https://www.amazon.com/author/davidbcoe